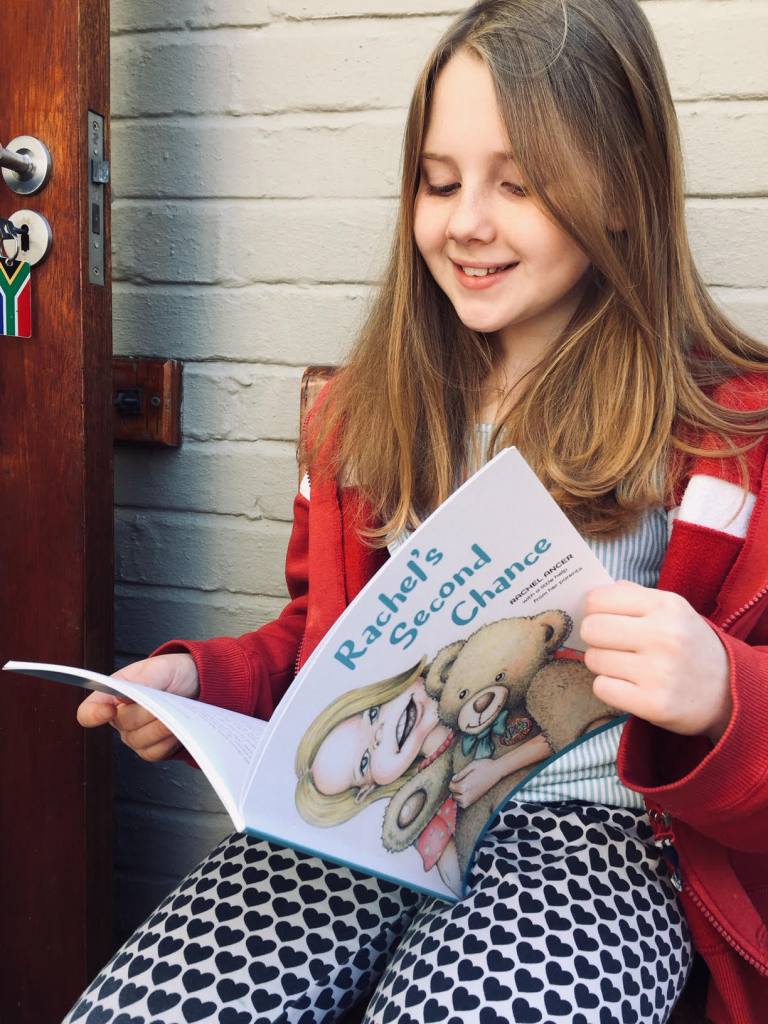

When my daughter Rachel was five she was diagnosed with a very rare bone marrow failure condition called Pure Red Cell Aplasia. Three years later, she had a life-saving bone marrow transplant. On 1 April 2023, her donor Magda Lewandowska travelled from Poland to South Africa and the two met for the first time. This is a little speech I gave at a tea to thank Magda and Rachel’s doctor at the Red Cross Children’s Hospital, Marc Hendricks, and Terry Schlaphoff, the former deputy director of the SA Bone Marrow Registry.

Today’s story starts in Gdynia, a city in northern Poland on the Baltic Sea. That’s where Magda Lewandowska – who may or may not be related to polish football star Robert Lewandowski – and her good friend Karolina Denc met on Saturdays for a weekly ritual of gym and dinner.

However, after gym on 5 November 2016, Karolina wanted to go on a detour to the Riviera Centre in Gdynia, because that’s where DKMS, an international organisation that recruits bone marrow donors, was holding a donor drive. Karolina wanted to join the registry but she wanted to do it alone because she didn’t want anyone to feel pressured into joining with her.

Nevertheless Magda insisted on accompanying her there. Magda told Karolina she wouldn’t join – she would just go to support her.

At the time, 35-year-old Magda was working in an IT company. When she wasn’t working she rollerbladed, rode horses, ran, cycled, went to the gym, travelled as often as she could – eating souvlaki in Greece was her favourite – and pampered Shrek, her extremely cute (and occasionally bad tempered) Jack Russel.

While Karolina’s blood was being taken, Magda thought that perhaps there was a reason that she was at the donor drive.

Perhaps she was meant to be there.

Perhaps there was someone who needed her to register.

So, at the very last moment, and despite Karolina’s request, Magda decided to register.

Magda was given a choice – she could join the Polish registry and her stem cells would be available for only local patients, or she could be an international donor – and her stem cells would be available to anyone in the world. She chose to be an international donor.

Magda’s blood went to be tissue-typed … and Magda went to dinner with Karolina.

The next day Magda returned to her job at the IT company (and rollerblading, horse-riding, cycling, gymming, running, pampering her extremely cute and occasionally bad-tempered Shrek, and plotting her next holiday).

Twenty days after Magda joined the DKMS registry, we celebrated Rachel’s 8th birthday in Cape Town – at that table, which is 14,088.2km away from the Riviera Centre in Gdynia. According to Google Maps, it will take 183 hours to drive there, via the Trans-Sahara N1 highway. So, if we left now we will get there on Tuesday 18 April at 3am.

For her 8th birthday, Rachel had chosen macaroni-and-cheese for her supper, but she didn’t eat any of it, she just stared at it, and pushed the poor mac-and-cheese around her plate. She didn’t have much of an appetite in those days and hardly ever ate.

Rachel was in Grade 1 at Herzlia Primary School. She had been a precocious, naughty, funny, smart, charming and cheerful chocolate-loving little girl but an exceedingly rare illness had robbed her of her bubbly, bouncy and carefree existence.

The illness – Pure Red Cell Aplasia – had caused her bone marrow to go on strike and not make red blood cells. When her haemoglobin levels dipped her skin became translucent, her lips turned blue and her heart beat like a machine gun in her chest. She was being treated with red blood transfusions.

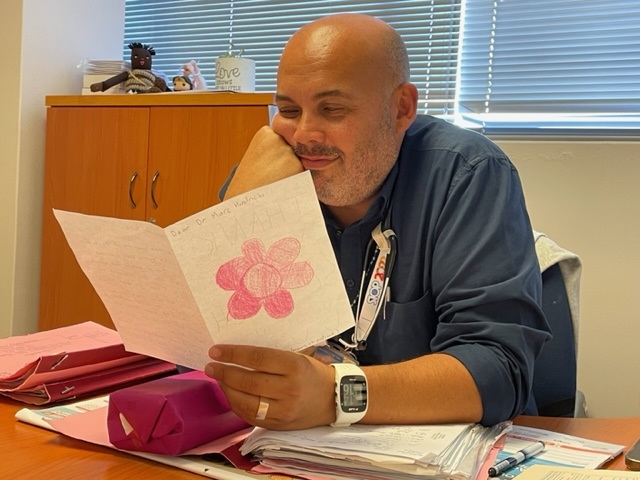

When we discovered that Rachel was ill we began a long medical trek. A lot of people became our cheerleaders, providing encouragement, support, prayers and hot meals – but one person walked with us every step we took on this difficult journey.

In fact, he didn’t just walk with us – he showed us the path.

It’s difficult to describe the role that Dr Marc Hendricks played on our journey. He was Rachel’s primary doctor at the Red Cross – but he was so much more than that. He answered all our questions no matter how silly they were (and some were very silly). He treated Rachel with such tenderness and held her and our whole family with the strength of a pride of lions.

We weren’t in good hands, we were in the best hands.

The doctors, nurses and lab technicians that we encountered have been unsung heroes not only to us but to so many very sick children with life-threatening illnesses.

Towards the end of 2015 Dr Marc told us that Rachel had become transfusion dependent and needed a bone marrow transplant.

That was when the SA Bone Marrow Registry (SABMR) and Terry Schlaphoff, who at the time was the registry’s deputy director, became involved. The Bone Marrow Registry crunched the data and found an impressive list of potential matches. They started doing high resolution tests to see which of Rachel’s possible donors would be her actual donor.

One by one, all the options mismatched.

Every morning Terry arrived at the Bone Marrow Registry’s office and rushed to the computer to see if one of the international registries had produced a new donor overnight that was a match for Rachel. But no luck. Days turned into weeks, weeks into months …

While we were waiting we heard Michael Bublé’s song, Just Haven’t Met You Yet – he was writing about the love of his life that he hadn’t met yet, but we somehow felt the song was about us – or more accurately, it was about Rachel and her donor.

I might have to wait // I’ll never give up // I guess it’s half timing // And the other half’s luck // Wherever you are // Whenever it’s right // You’ll come out of nowhere and into my life

In the meantime, the intervals between Rachel’s red blood transfusions were getting closer and closer together. Rachel survived from transfusion to transfusion – if you can call lying in a heap on the floor surviving.

Terry was beginning to lose hope of finding a match. She may have been losing hope but she wasn’t about to give up. Terry arrived at work on the morning of 23 December 2016 – the SABMR’s last day before closing for the year – and just like every morning, the first thing she did was to look to see if a donor for Rachel had joined the registry.

Bingo! There was a match. Terry described it as a “moment of magic”. I think it was a Hanukkah Miracle. Terry grabbed it and reserved the donor for Rachel.

A transplant was scheduled for 14 March 2017 so that Rachel’s bone marrow would stop making bad blood and start making good blood.

At 3pm on 14 March 2017, Magda’s stem cells were infused into Rachel – and magically and miraculously – rebooted Rachel’s faulty bone marrow. That moment brought four lives together: Rachel and Magda and Dr Marc and Terry.

There was a lot of serendipity that happened for that moment to take place: Magda insisting that she go with Karolina to join the registry and then deciding to join too. Out of all the doctors in the world, the one doctor we needed – happened to be just 3,5km away from us and he just happened to have a heart of gold and a smile that can light up a room (which is pretty useful during load shedding).

We have discovered that my grandfather, Chaim Ancer, came from a village in Poland just 30km from Magda’s grandmother’s village.

A freaky coincidence happened even closer to home. In fact, right next door. Our neighbour’s mother Ernette du Toit was the founder of the South African Bone Marrow Registry and Ernette’s mother had also had Pure Red Cell Aplasia – the only other person in South Africa that we know of with this diagnosis.

I’ve thought about how to describe these connections that led to that moment on 14 March 2017 – and the one word that keeps coming up is “miraculous”.

The miracle of medical science

The miracle of Dr Marc’s rare combo: his specialist medical expertise and his compassion.

The miracle of Terry’s perseverance

The miracle of Magda’s selflessness

The miracle of Rachel’s resilience – and her lion-like courage

It’s also a miracle of hope

I’m a copy editor at a news website and the news cycle often feels like the place where hope goes to die. It’s difficult not to feel overwhelmed, distressed and helpless when you read story after story about conflict, rage, load shedding, corruption, poverty, racism, xenophobia and violent crime. It’s difficult not to lose hope.

But when I think of the remarkable people who have made Rachel’s recovery possible – Dr Marc, Terry and Magda – my sense of hope in the world is restored

Which brings me back to Magda, Rachel’s donor; her genetic twin, her 10/10 match, who came into our lives in the nick of time.

On the 14 March 2017, when Rachel had the bone marrow transplant, Rachel and Magda became inextricably linked.

A day before the transplant Jean and I wrote a letter to Magda – at that time we weren’t allowed to know who she was. We wrote that there’s an unspoken bond that parents will do whatever it takes to look after our children and that she had allowed us to keep our promise to Rachel.

We wrote that we hadn’t met her yet but we hoped to meet her someday and that although we hadn’t yet found the words to express how grateful we are to her, we would like an opportunity to try.

Well, that someday was last week when Magda came to South Africa (and was nearly eaten by a lion – but that’s another story).

Magda, it’s six years later. We’ve been trying to find the words to thank you and to explain to you what your selfless act has meant to us, but we still don’t have the words. I’ve sat at my computer typing sentence after sentence after sentence… and then deleting them. And then I realised that the words don’t exist – because no words can adequately express our gratitude to you.

So, all we can do is to encourage people to follow in your example and join the Bone Marrow Registry and to dedicate Rachel’s rebirthday to you and Terry and Dr Mark and to all the selfless bone marrow donors, who give people a second chance, and who keep the miracle of hope alive.

Magda, dziękuję bardzo